As a software architect, it’s easy to get lost in technicalities, design patterns and implementation details. This often leads to your vision of the whole being blurred and obfuscated by building blocks that don’t really correlate with the system you are trying to design. Understanding that the whole is other than the sum of its parts, as Kurt Koffka once said, deeply affects our perception of the function imposed on those parts. If the whole is independent and has its own meaning, then what is the purpose of each one of those parts? None. They are meaningless, merely means to an end.

You can see where i’m going with this: a Factory, a Builder, a Strategy, they are nothing without the whole. And the whole has a purpose of its own, tied to the domain of our solution. Therefore, the purpose of the whole should never be tied to the intricacies of its parts. In Domain-Driven Design, Eric Evans introduces the term ubiquitous language, which is a common language between developers and users of a software, tied to its domain model. In order to achieve a good architecture, your whole should be able to communicate it’s meaning using this same language. And so does the parts.

In the early 1910s, Kurt Koffka worked with Wolfgang Köhler and Max Wertheimer on several theories that formed the Gestalt psychology, which attempts to understand how humans visually perceive the world surrounding them and describes how they tend to organize visual elements into wholes. When learning the psychology of design and essential concepts such as space, balance and visual hierarchy, i also learned the principles of Gestalt. Rudolf Arnheim, in his excellent book, explains in great detail the principles of similarity, proximity, continuity, closure and ground symmetry.

I highly recommend you to take some time and read more about design psychology and, specifically, Arnheim’s book. But for now, i want to focus on the principle of similarity:

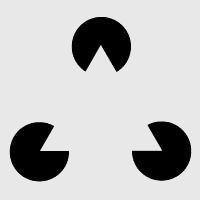

You see the triangle. But the triangle does not exist, only three pacman-like structures. The structures are meaningless, but what they compose has an enormous complexity of its own. And this is what makes great software architecture: a software application is not just the sum of each of it’s components, it’s something else, independent, with a purpose of it’s own. And it is your responsibility, as a software architect, to find this purpose.

This is what i call unified perceptual modeling: bound by the rules of the language of your domain, you must model your application using several components, yet always through the perspective of the whole. If you don’t see the whole and its purpose, you will never achieve consistency.